If I go to sleep now, I will get six hours of sleep … Expressions like this are all to common, and lead to one of the most self-destructive behaviours that societies around the world have accepted and embraced for too long. In this post I would like to talk about sleep, why we do it, how we do it, and the consequences of doing it wrong. I hope that at the end of this text I could have change your mind about your sleep pattern, or at least made you want to discuss it. If you already know that you have problems sleeping, have read information on it and are only looking for tips on how to improve your sleep, feel free to jump to the section 12 sleeping tips.

Many concepts that I present in this post have been presented more extensively in the book The way we sleep, this book presents many interesting concepts that I do not cover in this post. Such as a societal view on sleep, the effect of sleeping pills, the link between sleep deprivation and long term diseases, more details on the role of REM and NREM sleep, etc. One of the first questions that we might face is Just how much sleep is enough sleep?. Fortunately, there is a questionnaire that you can fill in order to figure out the quality of your sleeping patterns, it is called SATED.

Nothing but ticking clocks

Without further ado, lets jump into this topic. There are two main biological processes that regulate our urge to sleep, those are the circadian rhythm and homeostasis, the last one is just a fancy word for the sleep pressure that drives us to go to bed.

The circadian rhythms are biological clocks that function in a ~24h cycle, they control several of our body functions, such as temperature, wakefulness, etc. They are the ones responsible for making us wake up in the morning, if you are a lucky one. Our circadian rhythms also tend to synchronize with external signals from the environment such as light and temperature, but these clocks are able to continue functioning even in the absence of those signals. The perpetual ticking of or circadian clocks in the absence of environmental signals was tested to the limit by people like Michel Siffre, Kleitman and Richardson, who spent a couple of months underground without a watch and without light; who needs a watch if you don’t have light to see it?. During this period, Michel lived a very strange life, where his sleeping cycle varied between 15 to 40 hours, proving that our internal clocks like to follow a cyclic sleeping pattern, even when we are deprived of environmental signals. I can only imagine what kind of thoughts were going around in Michel’s head during those weeks of isolation underground.

The second internal clock in our system is the sleep-awake homeostasis (sleep pressure). This is an internal mechanism that keeps track of how much sleep we have had and therefore how much are we in need of. This sleep pressure is mediated by a molecule called Melatonin, for every hour that we are awake, Melatonin builds up in our brains, and it is only disposed of when we go to sleep. This means that for as long as we are awake, Melatonin keep piling up, causing us to feel sleepy. Something interesting about Melatonin is that its the level of production and disposal efficiency varies a lot across our lifespans. When we enter our teenager years, Melatonin release is delayed, which then shifts the bed time and waking hours. Most of us might have gone through that phase of life where all we wanted to do was to sleep in, and maybe some of us never left that phase. As we get older, our bodies produce less Melatonin and do not process it so well, which might also explain why older people have more insomnia-related problems, grandpa might be able to testify to that.

Both the circadian rhythms (sleep-driven) and sleep-awake homeostasis (wake-driven) are usually synchronized in order to regulate when we sleep and when we are awake. The bigger the different between them is, the bigger the desire to sleep (figure below). As long as these two clocks are synchronized, our sleeping patterns remain more or less regular, the problems start to realize when we force these internal clocks to go out of synchronicity.

The combination of two biological processes drives our urge to sleep. The bigger the gap between both clocks, the bigger the urge to sleep.

Fooling our brains

Did you ever feel that if you sleep a few hour less, you feel more awake the day after? I have to disappoint you here, because this is more an illusion of wakefulness rather than actually being more awake. Remember the sleep-awake homeostasis? The longer we are awake the more Melatonin is accumulated (pink line). When we decide to shorten our sleep by a few hours, or not sleep at all, we are depriving our bodies from the hours that it needs to get rid of the excess of Melatonin. Once we wake up the day after, our circadian rhytms kick in and we start to feel a surge of energy and wakefulness. However, this is only caused by a transient decrease of the gap between the circadian rhytms and our Melatonin-driven clocks, even though the Melatonin concentration is still much higher than our bodies realize. Once the effect of the circadian rhytms decreases at night, the desire to sleep emerges again, this time a lot stronger than the night before.

The reason why sometimes we feel awake even after not having slept is due to a misalignment of the two biological processes that drive our urge to sleep. This is only a transient state and does not really represent that we are rested.

If you would like to learn more details about sleep, I recommend to look into the Brain basics - NIH webpage.

The sleeping cycle

A lot has already been written about the sleeping cycle, and I believe that other sources have described it in detail in a marvelous way. Here I merely attempt to describe it in a short manner; if this sparks your curiosity, I will leave some links to great resources below.

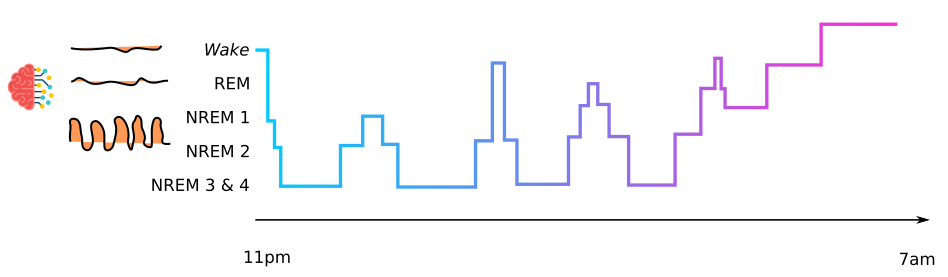

While we sleep, our brains go into a cycle that are differentiated mainly by the brain activity. Generally, each one of us would go through 4 to 6 of these cycles during night, provided that we sleep around eight hours each night. Most of us are familiar with the main sleeping phases REM (rapid eye movement) and NREM (non-rapid eye movement). During these two phases, our brains behave in very different ways. As the name indicates, the REM sleeping phase is the part of our night that is characterized by the rapid movement of our eyes, it is also the phase where our brains create an entirely new reality, we call that new reality a dream. Contrary to what most of us might believe, most of us will dream during night, unfortunately, many of us will forget our dreams even before we awaken. But you can take comfort in the fact that your dreams are there, even if we can not remember them on demand. NREM is the other part of our sleeping cycles, which is characterized by an immense boost in brain activity. During NREM sleep, there are, quite literally, immense tsunami-size (slow) electric waves traveling from the front to the back of our brains. If we were to place electrodes in our skulls and measure the brain activity during sleep and compare it to the activity during day, we would observe something like in the figure below. While we are awake, our brains electrical activity is rapid, but with a small amplitude, which is very similar to the activity we would observe when we in REM sleep. There is a lot of disagreement regarding why we have evolved to have these particular brain activity patterns while we sleep. One of the most popular ideas is that during REM sleep, our brains go into creative thinking, where we try out new ideas to solve problems in creative and unprecedented ways. Another popular theory indicates that NREM sleep is particularly tailored to the learning process, where those slow tsunami-sized electric waves transport the knowledge we have gained during the day from the temporary storage of the brain to the long-term storage. We thought for a very long time that sleep is a condition that characterized humanity, however, like in many other occasions, we were wrong. We now know that many other species also dream and show similar sleeping patterns as we do. It seems that the life, in its entirety, is closely linked to sleep.

The sleeping cycle can be more chaotic that we might expect it, sometimes even skipping phases during a cycle. However,

the general trend remains.

The sleeping cycle can be more chaotic that we might expect it, sometimes even skipping phases during a cycle. However,

the general trend remains.

Another interesting fact about the way we sleep has to do with our physiology. Right before we fall asleep, the temperature of our bodies decreases a couple of °C, this aids in driving our brains into the first sleeping cycle. This might also be the reason why many people, me included, find it a lot easier to fall asleep in cold rooms or during winter. Another link to the physiology of our bodies is the role that our nervous system takes while we sleep, more precisely during REM sleep. Our brain quite literally numbs of limbs to prevent us from taking physical action during our dreaming phase of the night. In most cases we do are unaware of this state while we sleep, however, there are exceptions. There are occasions when we are falling asleep or waking up, that our brains mess up and enter the paralysis state while we are awake, this is know as sleep paralysis. Up to 50% of us experience sleep paralysis at some point during our lives, but only around 5% of people have recurring episodes. If you have experienced this before, you might agree with me that it is not a pleasant experience.

Further reading:

- Sleep cycle: More in depth reading about the different sleeping phases

- REM sleep: More details on REM sleep

- NREM sleep: More details on NREM sleep

Sleep deprivation

We might not know at this moment what particular role each of the sleeping phases plays in our lives but we do know that we can not live without them. Depriving ourselves from a good night sleep can have dire consequences, which can range from lower performance in critical thinking to more life-threatening risks, which is why the Guinness World Records no longer keeps track of attempts to self sleep deprivation. The fact that this got too extreme for the Guinness World Records, while breaking the sound barrier during free fall is still allowed, should tell us a lot about how serious this is. There have been many experiments trying to determine how much sleep a person can spare before a cognitive decline is observed. The short answer: there is not such thing as safe sleep-deprivation. It was shown several years ago that reducing your amount of sleep by a couple of hours has the same effect has drinking two beers. Reduce your sleep by one more hour and you are over the legal driving limit, unfortunately there are no sleep breath analyzers, and even if they existed, I don’t think that it would be implemented in the near future. This is unfortunate news for many people that have jobs in sectors of our society that are at risk of suffering constantly fom sleep deprivation, such as truck drivers, first responders, medical staff, etc. Allow me to paint you a mental picture, if you had a surgery scheduled, and you find out that the surgeon in charge of your procedure has had 2 beers before your operation, would you sincerely feel comfortable going under his knife? This is something that you might have consider, given the fact that it is common practice for medical staff to pull of long shifts without benefiting from those sorely needed hours of sleep. The false notion that less sleep and more work makes us more productive is something that has found a niche in many modern societies, and I believe that it is time to abolish that notion.

Sleeping misconception

- Is the brain resting while asleep?: No, in fact, our brains go into hyperdrive while asleep. There are many vital biological processes that happen while we sleep. Many of these processes are related to creative and rational thinking as well as the process of learning new things. Our bodies can consume between 400 to 600 calories while sleeping, so don’t feel bad about sleeping, your body/brain is still doing a lot of work.

- Can we afford to sleep one hour less every day?: No. This is probably one of the most common misconceptions. We definitely can not afford to reduce our sleeping hours by one hour every day, the negative effects of sleep deprivation only accumulate and we can not recover from them by simply sleeping longer on weekends. There is no such thing as recovering sleep!.

- Can we afford to study until late before an exam?: NO!, a good night sleep is closely tied to the learning process. Many studies have indicated that the NREM sleeping phases boost the learning process. More interestingly, a good night of sleep after learning something new is just as important as a good slumber the day before.

12 sleeping tips

I here present 12 sleep tips that were published in the NIH back in 2012. IF you would like to get more information in this matter, you can visit this website. My advice to you, if you want to try these tips is: don’t try to implement them all at once. Select five tips that you believe that you can actually implement and stick to them, like pollen to a bees ass. Try them for at least one month and I am most certain that you will notice the difference.

- Stick to a sleep schedule. Go to bed and wake up at the same time each day. As creatures of habit, people have a hard time adjusting to changes in sleep patterns. Sleeping later on weekends won’t fully make up for a lack of sleep during the week and will make it harder to wake up early on Monday morning. Set an alarm for bedtime. Often, we set an alarm for when it’s time to wake up but ail to do so for when it’s time to go to sleep. If there is only one piece of advice you remember and take from these twelve tips, this should be it.

- Exercise is great, but not too late in the day. Try to exercise at least thirty minutes on most days, but not later than two to three hours before your bedtime.

- Avoid caffeine and nicotine. Coffee, colas, certain teas and chocolate contain the stimulant caffeine, and its effects can take as long as 8 hours to wear off fully. Therefore, a cup of coffee in the late afternoon can make it hard for you to fall asleep at night. Nicotine is also a stimulant, often causing smokers to sleep only very lightly. In addition, smokers often wake up too early in the morning because of nicotine withdrawal.

- Avoid alcoholic drinks before bed. Having a nightcap or alcoholic beverage before sleep may help you relax, but heavy use robs you of REM sleep, keeping you in the lighter stages of sleep. Heavy alcohol ingestion also may contribute to impairment in breathing at night. You also tend to wake up in the middle of the night when the effects of the alcohol have worn off.

- Avoid large meals and beverages late at night. A light snack is okay, but a large meal can cause indigestion, which interferes with sleep. Drinking too many fluids at night can cause frequent awakenings to urinate.

- If possible, avoid medicines that delay or disrupt your sleep. Some commonly prescribed heart, blood pressure or asthma medications, as well as some over-the-counter and herbal remedies for coughs, colds, or allergies, can disrupt sleep patterns. If you have trouble sleeping, talk to your doctor or pharmacist to see whether any drugs you’re taking might be contributing to your insomnia and ask whether they can be taken at other times during the day or early in the evening.

- Don’t take naps after 3 pm. Naps can help make up for lost sleep, but late afternoon naps can make it harder to fall asleep at night.

- Relax before bed. Don’t over-schedule your day so that no time is left for unwinding. A relaxing activity, such as reading or listening to music, should be part of your bedtime ritual.

- Take a hot bath before bed. The drop in body temperature after getting out of the bath may help you feel sleepy, and the bath can help you relax and slow down so you’re more ready to sleep.

- Dark bedroom, cool bedroom, gadget-free bedroom. Get rid of anything in your bedroom that might distract you from sleep, such as noises, bright lights, an uncomfortable bed or warm temperatures. You sleep better if the temperature in the room is kept on the cool side. A TV, cell phone or computer in the bedroom can be a distraction and deprive you of needed sleep. Having a comfortable mattress and pillow can help promote a good night’s sleep. Individuals who have insomnia often watch the clock. Turn the clock’s face out of view so you don’t worry about the time while trying to fall asleep.

- Have the right sunlight exposure. Daylight is key to regulating daily sleep patterns. Try to get outside in natural sunlight for at least thirty minutes each day. If possible, wake up with the sun or use very bright lights in the morning. Sleep experts recommend that, if you have problems falling asleep, you should get an hour of exposure to morning sunlight and turn down the lights before bedtime.

- Don’t lie in bed awake. If you find yourself still awake after staying in bed for more than 20 minutes, or if you are starting to feel anxious or worried, get up and do some relaxing activity until you feel sleepy. The anxiety of not being able to sleep can make it harder to fall asleep.